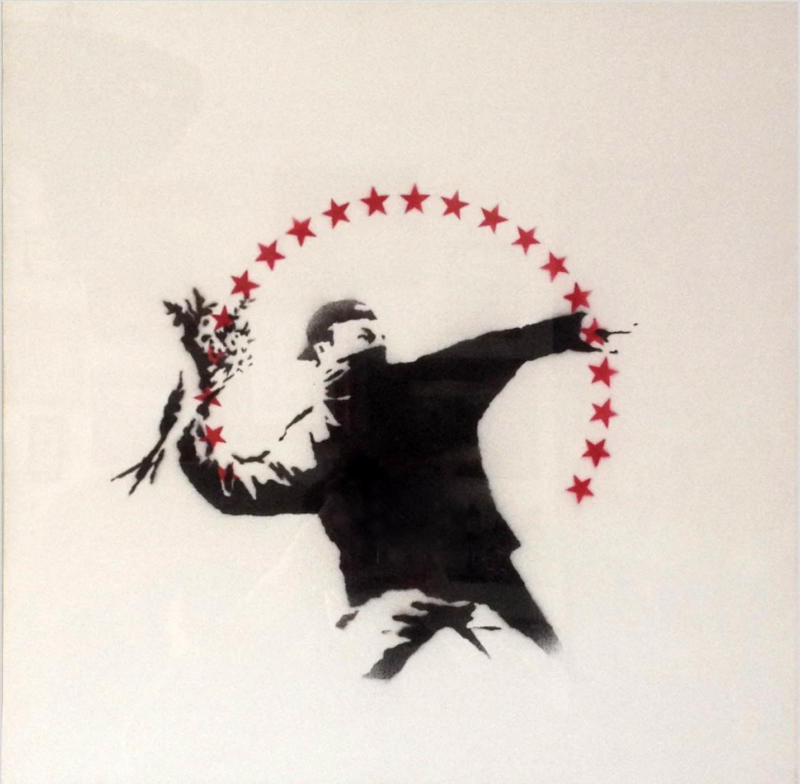

Love Is In The Air (with Stars), 2003

Edition: 25

Stencil spray-paint on canvas

50.8 x 50.8 cm (20×20 inches)

Stenciled “BANKSY” in red spray paint on the lateral edge

Further dated and numbered /25 on the stretcher

Presenting a twist on one of Banksy’s most iconic images, Love is in the Air (with stars) is a rare iteration of his seminal ‘flower thrower’ motif. Executed in 2003, the year after the original mural first appeared on the side of a garage near the newly-erected West Bank barrier wall, it represents an extension of the image’s call for peace in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Banksy’s masked insurgent leans backwards, as if preparing to hurl a weapon; instead, his hand is clasped around a bunch of flowers.

The present work is distinguished by a halo of red stars that circles the figure, tracing the projected arc of his floral missile: like Andy Warhol’s silkscreens, the image is uniquely rendered, sprayed through a hand-cut stencil.

Sharing its title with the 1978 John Paul Young hit, the work’s blend of irreverent humor and socio-political commentary positioned Banksy on the world’s stage, encapsulating his belief that art should be a force for global change. As with many of his creations, the work continues to resonate beyond its original context: with the conflict ongoing, most recently escalating with the tragic outbreak of violence in May 2021, Love is in the Air remains one of the twenty-first century’s most poignant and enduring images.

Widely reproduced—notably on the cover of his 2005 monograph Wall and Piece—Banksy’s original Love is in the Air mural was first painted in Beit Sahour, a town in Palestine just east of Bethlehem. The West Bank barrier wall and the surrounding area has since become a site of continued activism for the artist: multiple instances of his work pepper the region, including his 2005 mural Balloon Debate, depicting a small girl being carried over the wall by a bunch of balloons. In 2017, Banksy designed the infamous Walled Off Hotel opposite the barrier—billed as having ‘the worst view of any hotel in the world’—in a bid to amplify tourist awareness of the region’s ongoing unrest. Within this network of creations, however, Beit Sahour remains a site of particular significance: in Christian tradition, it is said to be the location at which the Annunciation to the shepherds took place, alerting them to the birth of Jesus. Interestingly, the pose of Banksy’s protagonist recalls that of the angel statue outside the town’s Shepherds’ Fields Chapel—whose arm similarly points into the distance—enhancing the work’s sense of hopeful prophecy.

Banksy’s circle of stars, curiously redolent of the Paramount Pictures logo, may also be seen to play into the image’s message of support. Used in a number of works during his early practice, the motif recalls the symbolic crown of stars that is frequently depicted above the Virgin Mary’s head, representing the twelve Seraphim Angels assigned to protect her. This strand of iconography would later be co-opted by Arsène Heitz, one of the designers of the European flag, who proposed a similar ring of yellow stars as a symbol of unity and harmony—ironically, Banksy himself would riff upon the latter in his anti-Brexit mural of 2017. Such associations are further enhanced by the motif of the bunch of flowers, which—in taking the place of a bomb, brick or other instrument of assault—evokes the sentiment of the Flower Power movement and the associated anti-war demonstrations in America during the 1960s. Images from the time show protestors offering flowers to military police, and—in a landmark Pulitzer Prize-nominated photograph of 1967—placing carnations inside their rifle barrels.

In its oscillation between imagery of rebellion and peace, the work speaks directly to Banksy’s own mission as a graffiti artist. From his early days tagging the streets of his native Bristol, to his subsequent projects at sites around the world, he has viewed the medium as a means of non-violent disruption: a vehicle for social and political critique that ultimately returns art to the people. His images live within the world, reflecting its struggles and triumphs; liable to be erased at any moment, they are as fleeting and elusive as the artist himself. Banksy’s signature use of hand-cut stencils—a technique first inspired by observing the lettering on the underside of a rubbish truck while hiding from the police—is part and parcel of this notion, infusing his works with a bold, anarchic edge. Yet for all its apparent lawlessness, Banksy’s approach is ultimately one of outreach: like flowers hurled into a warzone, his works represent beacons of hope for those whose lives they reflect. With his face partially concealed by a mask, the present work’s protagonist might be read as an extension of the artist himself: an anonymous insurrectionary, throwing tokens of comfort, surprise and solidarity into the void.